Introduction

Bleak House was a 692‑acre plantation nine miles northwest of Charlottesville. Dr. James B. Rogers (1793‑1863) purchased it from the heirs of William Michie in 1836 and built the house, which still stands, about 1854. The plantation bordered the South Fork of the Rivanna River about five miles upstream from the Hydraulic Mills. Wheat, tobacco, corn, and livestock were raised there and activities included blacksmithing and textile production.

Plantation Owners: The Rogers

Dr. James B. Rogers, who attended University of Pennsylvania medical school, was married in 1819 to Margaret Wood, daughter of David Wood and Mildred Walker Lewis. Only two of their many children, William G. Rogers and Martha Rogers Wood, wife of Dr. Alfred Wood, left descendants.

In this article we will use two examples to demonstrate how to uncover information about African Americans who were enslaved at Bleak House Plantation. The first example – Mariah – will start with antebellum records (specifically a Slave List from an estate inventory) and move forward in time (“The Path Towards Freedom”). To explore the opposite approach (“Searching for Enslaved Ancestors”): researching someone from a known family and trying to trace their ancestry backwards, visit the Allen and Judy Reed example.

For additional Information about the Enslaved People at Bleak House visit Alice Cannon’s visualization of this community.

Bleak House Plantation African-American Population

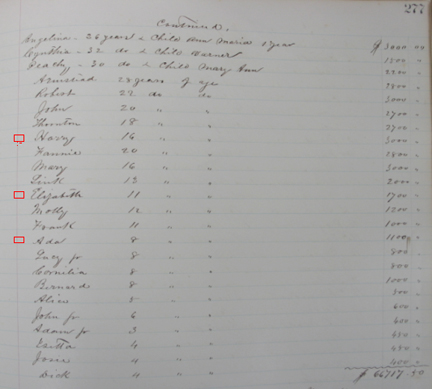

In 1860 the Bleak House plantation had 41 slaves and 9 slave dwellings. The inventory of Rogers’s estate (1864) includes 36 slaves (fiduciary accounts note 14 others advanced to Rogers’s children and a grandson between 1845 and 1863). His son William G. Rogers was executor of the estate, which was involved in lawsuits and legal complications into the twentieth century. An estate sale in late 1863 did not include any slaves.

In 1870, Bleak House became the property of S. V. Southall, who sold several parcels of land to freedmen in the area nearest to Earlysville and Michie’s Old Tavern (relocated in the 1920s near Monticello). In the 1870 census, several African‑American families appear near each other in what seems to be a community of former Michie and Rogers slaves. This community continued until the mid‑twentieth century.

The Path from Slavery to Freedom

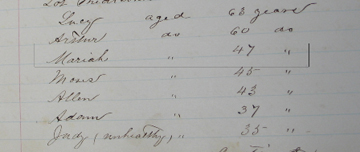

To research the African Americans who lived on the Bleak House plantation we started with the inventory and appraisal of Dr. James B. Rogers’s estate (May 1864; Albemarle County Will Books). There is no record that any slaves were sold out of the estate before Emancipation.

‑‑Search for Mariah‑‑

For this search we selected one woman from the inventory:

Mariah, aged 47, value $1000. (b. 1816.)

Tracing women from slavery to freedom can be more challenging than tracing men—especially so in this case where the first name is common and the inventory does not group slaves by family. The Albemarle County Personal Property Tax List (PPTL) cannot be the first step, as it was for Thornton Tyler of Hydraulic, because it lists only males (and some females who were heads of households).

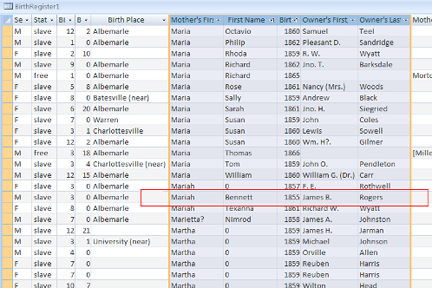

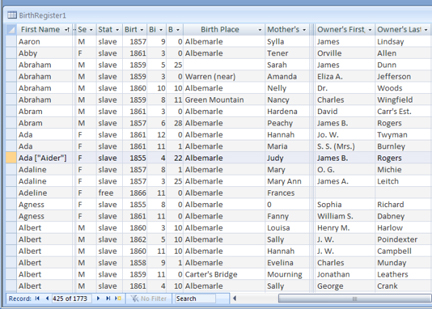

Instead, to achieve a cluster of first names to search in censuses, we usually start by looking at the birth records database, sorting by mother’s and owner’s names. Only one birth was found for a Maria/Mariah owned by James B. Rogers: “Bennett” born in 1855.

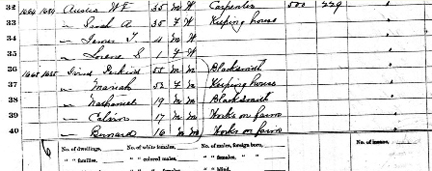

There is no Bennett in the Rogers inventory or fiduciary accounts, but there is a Bernard, age 8, and thus born c. 1855. When pronounced, the two names are quite similar. So, next we try looking for a Bennett or Bernard, born about 1855, in the 1870 census. We found no relevant Bennetts, but two possible Bernards: Bernard Ivins and Bernard Jennins. When we examine the original pages, it becomes clear that this was a double record of a family headed by Perkins Ivins/Jennins, a blacksmith, his wife Maria, and several children (with inconsistent first names)(Figure 3). There is a 90-year-old Hannah Wood living with them, who matches a Hannah, age 85, in the Rogers inventory. She is thus likely to be Maria’s mother.

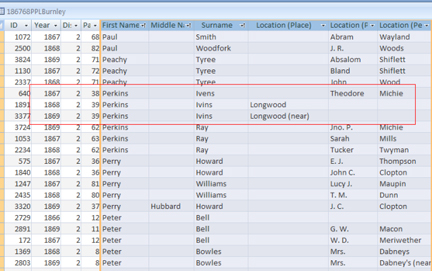

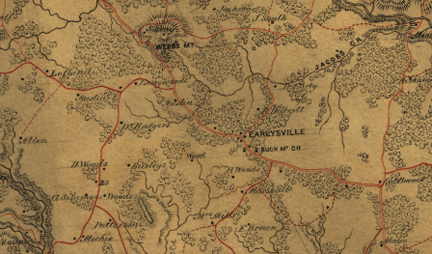

Now we need to determine what is the family’s actual surname. Sorting the PPTL by first name for “Perkins” reveals a Perkins “Ivins” or “Ivens” living from 1867 to 1869 at or near the “Longwood” estate of Theodore Michie (Figure 5). On the 1864 Civil War map of Albemarle County that we have geo-registered, Longwood appears as a plantation not far from Bleak House (Figure 6).

Later censuses resolve the family surname to Evans. The post-war location of Perkins Evans, who was not in the Rogers records, suggests that he might have belonged to the Michies of Longwood. The Will Books include an 1847 inventory of the estate of Theodore Michie’s father, James Michie, Jr. It lists a 32-year-old blacksmith named Perkins.

Now we have the basic information about the family of Perkins and Maria Wood Evans and can explore additional records. In their case, marriage records, death and burial records, later censuses, personal papers, and a surviving Evans graveyard, helped to fully fill out the family tree. One of their sons, Nathaniel ‘Link’ Evans, was a well-known Earlysville blacksmith; there is now a Link Evans Road in the area. Contact has also been made with Evans descendants, who shared a rich oral history that shed important light on Maria (Wood) Evans’s early history, as well as the lives of her descendants.

The Search for Enslaved Ancestors

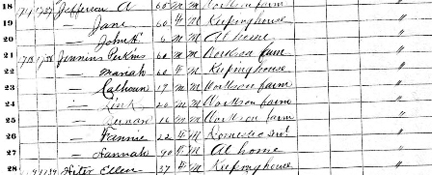

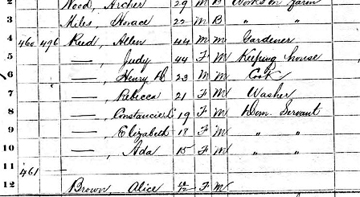

Suppose someone has traced their ancestry to Allen and Judy Reed (both aged 44) in the 1870 census for Fredericksville Parish (see Figure 1 below). The couple is listed with five children, Henry, Rebecca, Constance, Elizabeth, and Ada (aged 23 to 15), and all are mulatto. Allen Reed is a gardener. The largest landholders nearby are Mary Harper and Warner Wood.

To begin tracing this family backwards in time, we turn to the birth records database to see if two or more children can be found with a mother Judy. There are three Adas, but only one (spelled “Aider”) of the right age (Figure 2). She was born to a “Judy” belonging to James B. Rogers. We next sort by Rogers to see if Judy had other children that match the census.

Only one other child born to Rogers’s Judy is present: Billy born in 1857, who is absent from the 1870 census.

On the strength of a mother-daughter Judy-Ada match, we look at pre-Emancipation Will Book records and find an inventory of James B. Rogers, May 1864 (Figure 3). It (and associated fiduciary accounts) contains adults Allen and Judy and children matching the 1870 census: Henry, Rebecca, Constance (“Connie”), Elizabeth, and Ada.

Now that we have confirmed the Reed family’s location in slavery, we can fill in their family tree with information from the marriage and other records (Henry Daniel Reed became a grocer and married Mary Sellars; Ada Reed married Vick Rives). A sort of the Personal Property Tax List (PPTL) reveals that Allen Reed and his family lived at Warner Wood’s in the 1867-1869 period. Wood was James B. Rogers’s nephew.

Expanding the search could possibly reveal the names of Allen and Judy Reed’s parents.